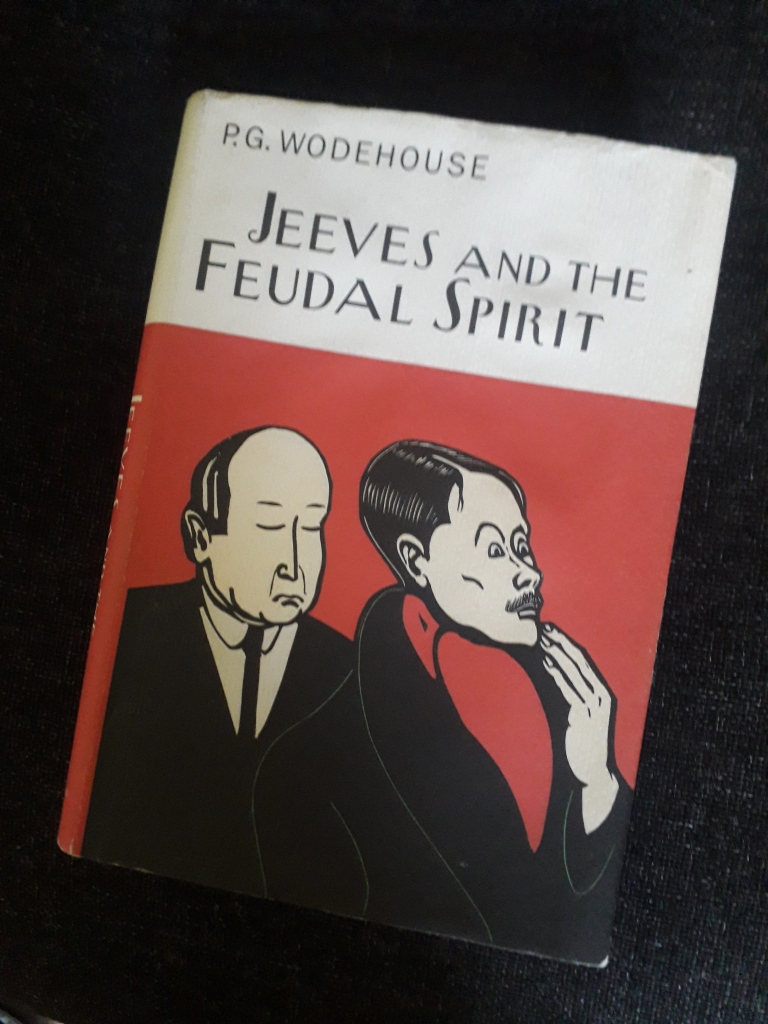

In 1954 P.G. Wodehouse published another novel. Well, why wouldn’t he? He was only 73, and the novel that he wrote – Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit – was only (by some accounting) his seventy-second book and only the seventh full-length Jeeves-and-Wooster story. (There had been many more short stories, and there were to be four more J-and-W novels before he died in 1975.) And as my illustration shows, I read this story in its recent Everyman hardback incarnation – a delight. Nice cover, nice design, nice typeface.

I’ve been enjoying Wodehouse’s work, especially the Jeeves and Wooster stories, for over 50 years myself, so it was no hardship to go back to this novel for the online #1954Club. Or was I not going back, but rather reading it for the first time? It’s difficult to be sure, for Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit (hereinafter JATFS) contains almost all the elements of previous stories featuring the duo: an aunt (Aunt Dahlia, the one who is the proprietor of the improbably named weekly Milady’s Boudoir and is ‘inclined to talk to you … as if she were addressing some crony a quarter a mile away whom she has observed riding over hounds’); a country house (Brinkley Court) where much of the action takes place; a young woman who mistakenly but only temporarily becomes engaged to Bertie (in this case it’s Florence Cray, who first appeared in Carry on Jeeves); and a hare-brained scheme that is doomed to fail until rescued by Jeeves.

The general consensus is that the best – that is, the funniest – Jeeves and Wooster novels are three that he wrote from the mid-1930s to the mid-1940s – Right Ho, Jeeves, The Code of the Woosters and Joy in the Morning – and it’s almost as if this later novel is determined to borrow as much as is legitimately possible from these earlier successes. Not that such borrowings detracted from my enjoyment. Indeed, one comes to relish those snatches of dialogue that seem to echo earlier exchanges: for instance this passage:

‘Your tie, sir. It will not pass muster.’

‘Is this a time to talk of ties?’

‘Yes, sir. One aims at the perfect butterfly shape, and this you have not achieved. with your permission, I will adjust it.’ (p100 in Everyman edition)

Compare this with (from the earlier The Code of the Woosters):

‘There are moments, Jeeves, when one asks oneself, “Do trousers matter?”’

‘The mood will pass, sir.’

Certain other motifs recur, such as Jeeves’s cough. In The Inimitable Jeeves (1923) he ‘coughed one soft, low, gentle cough like a sheep with a blade of grass stuck in its throat’; in JATFS it’s ‘that deferential cough of his which sounds like a well-bred sheep clearing its throat on a distant mountain-top’ (p213). The addition of the ‘distant mountain-top’, I think, is an improvement.

Incidentally the novel’s US title, Bertie Wooster Sees it Through, is perhaps more appropriate: the word ‘feudal’ doesn’t crop up much. There’s an early passage where Bertie is surprised that Jeeves is willing ‘to do the feudal thing’ and lie on his master’s behalf (p37), and another where Bertie is sure that ‘Feudal fidelity would no doubt make Jeeves seal his lips’ (p212). But otherwise feudalism doesn’t really feature.

What then is the appeal of Wodehouse, and in particular the Jeeves and Wooster cycle? Partly it’s the tone of voice, the fact that the story is narrated by someone (Bertie Wooster) who isn’t always aware of what is going on, and is served by someone who is intellectually superior but socially inferior (Jeeves), able to supply the mot juste when his master can’t. While their tight construction is often commended, the plots of Wodehouse novels are often seen as escapist – belonging to an ‘idyllic world’ whose characters ‘live in their own universe like the characters of a fairy story’ (Evelyn Waugh) or evoking an ‘atmosphere … [that] shows little alteration since about 1925’ (Orwell). Similarly Benny Green, in his P.G. Wodehouse: A Literary Biography (1981) wrote that ‘in his fictions, England slumbers through an Edwardian afternoon, never to be disturbed’. But that’s not quite right.

Agreed, Wodehouse did write, in a letter, that ‘I go off the rails unless I stay all the time in a sort of artificial world of my own creation. A real character in one of my books sticks out like a sore thumb’. But as D.A.N. Jones, in a LRB review of Green’s book, commented in quoting the letter: ‘This need not be taken literally. Wodehouse is putting himself down’ (If you can access it, I recommend reading the whole review).

Although the Wodehouse world is an artificial one, the ‘real’ world does intrude. There is, for instance, the well-known parodying of Oswald Mosley’s blackshirts in The Code of the Woosters, where Roderick Spode is mocked for his leadership of the fascist group The Saviours of Britain, known as the Black Shorts. (Which is relevant to another of D.A.N. Jones’s comments, that Spode ‘fits in prettily with Benny Green’s feeling that Wodehouse is an inspiration to anyone who is hostile to bullying and bossiness’.) Meanwhile, to return to JATFS, the 1954 novel has just enough up-to-date allusions to indicate that our author is not completely out of touch. W.H. Auden and T.S. Eliot are mentioned in connection with Florence’s authorial ambitions (p141); Bertie refers to David Niven (p15) when defending his decision to grow a moustache;* while his hyperbolic description of a police station as the home of ‘the Vinton Street Gestapo’ (p56) suggests a post-war sensibility.

Still, there are some elements of the plot that seem unlikely even within the make-believe world of Wooster. There’s Jeeves’s sudden revelation of his expert ability to distinguish between real and fake pearls (‘I spent some months at one time studying jewellery under the auspices of a cousin of mine’, p115), for instance; and would Bertie be able to drive down from Brinkley Court (which is in Worcestershire) to London in the late morning and be back in time for dinner (chapters 15-16)?

A final note: I owe some of what I’ve written here to a well-thumbed secondhand copy of Wooster’s World by Geoffrey Jaggard. And in my time I’ve also got through the American academic Kristin Thompson’s Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes; Owen Dudley Edwards’s P.G. Wodehouse: A Critical and Historical Essay and dipped into Robert McCrum’s thick biography. There’s still a lot of actual Wodehouse books I have yet to read, though.

*Those in the know would have been reminded that a young David Niven played Bertie Wooster (with a moustache) in the 1936 Hollywood film Thankyou, Jeeves (whose plot apparently owed little to the book whose title it shared).

A review worth sharing among all PGW fans. Although specifically looking at JATFS, it is sufficiently general to provide insights to Plum’s works in general.

LikeLiked by 1 person